Blog

Blog

What are the keys to successfully implementing batch management system?

15th January 2026 - News

Handling production in batches longer than one week (MEB>1s) has become an essential tool in modern pig farms, especially for health reasons. In Spain, the pressure from PRRS, especially the Rosalía strain, has promoted the adoption of MEB > 1 systems, which improve health control and work organisation. To learn firsthand about the factors that directly impact this system's success, I'm going to work with Carles Casanovas, a veterinarian specialising in pig production.

Carles Casanovas, veterinarian specializing in pig production. Photo: C.C.

When implementing a weekly batch management system, what factors determine the most suitable batch type?

The first is animal welfare, as it requires weaning at 28 days. Therefore, the MEB2s and MEB4s systems are unsuitable, since they involve weaning at 21 days. Furthermore, with current restrictions on antimicrobial use and the elimination of zinc oxide, weaning so early is often problematic. If PRRS is spreading, such young piglets suffer much more. That's why, beyond welfare considerations, the general trend has been to extend weaning to 28 days. Twenty or 30 years ago, most farms weaned at 21 days, but today most do 28 days. Therefore, the remaining options for weaning at 28 days include the MEB3s, the MEB5s, and variations of this system (MEB3/2s and MEB2.5s). The following criteria for deciding on the type of MEB >1s are the degree of grouping required to achieve an All-In, All-Out (AI-OO) operation by batch. The potential for reduced stocking density is a significant factor, which is why MEB3s are often a more challenging option to implement.

How do farm size and the number of farrowing rooms influence the system's design and viability?

If you operate with a four-week farrowing rotation, you can have more sows on the farm than with a five-week rotation, as you produce the same number of farrowings in a shorter time interval. For example, 100 farrowings every four weeks are not the same as 100 every five weeks. By switching to a five-week rotation, you lose approximately 20% of production. Since most farms today wean at 28 days and operate with five-week farrowing rotations, switching to MEB5s results in minimal production loss. In contrast, with MEb3s, the rotation period is extended to six weeks, which reduces farrowings and requires building more farrowing pens or having fewer sows. From a health perspective, MEB5s are very effective because they allow for TD-TF management with a single batch per farrowing room, whereas with MEB3s, MEB/2s, and MEB2.5s, two batches would be housed together. The same applies during the transition period. Furthermore, farm size itself should not be a determining factor. Traditionally, MEB>1s was associated with small farms to group tasks and achieve a higher volume of animals of the same age. Implementing it on large farms did not require this, as the production volume per batch was already high. Ultimately, the sow-to-worker ratio is the same, whether the farm is large or small, but large farms likely require greater coordination among all personnel. The number of rooms is particularly relevant when we want to implement MEB3s, MEB3/2s, and MEB2.5s, because an odd number of rooms means there will always be one room that does not work TD-TF.

“From a health standpoint, the main benefit is the ability to work with an All-In/All-Out system by production stages (farrowing and nursery).”

What structural and planning requirements must a farm meet to implement batch management successfully?

Again, it depends on the chosen system. If we start with MEB1s weaning at 28 days, switching to MEB3s means either increasing the farrowing capacity or reducing the stocking rate. If the stocking rate reduction is accepted, there will be no space problems; in fact, there will be excess space in the gestation area. However, if the farm switches to MEB5s, the opposite occurs: the number of farrowings remains more or less the same, but since many sows are weaned at once, this necessitates more space in the gestation area. For example, a farm with 120 farrowing spaces (five rooms of 24) that previously weaned 24 sows per week will have to move all 120 sows at once with MEB5s. In other words, it will need more gestation spaces to empty and clean the farrowing area. Expanding the gestation area becomes a basic structural requirement. When this isn't done, problems arise because the only option is to wean in stages, moving the sows in batches to gain space. This shortens sanitary breaks and can contribute to neonatal diarrhoea. Another key aspect is the transition period. Many farms are designed to keep piglets for 7-8 weeks, but with MEB5s, we have too much space if there's only room for one batch (and the piglets go to fattening at 14-15 kg, too small), or we have to extend the transition period if we want to house two batches, which then means removing very large piglets.

What benefits does this system offer in terms of health and work organisation compared to continuous management?

In terms of health, the main benefit is the ability to use a phased TD-TF system (farrowing and transition), which prevents animals of different ages from being in the same production area. This reduces the circulation of pathogens between batches, which significantly improves health. With MEB1s, on the other hand, new piglets, which may be negative for PRRS or other diseases, are continuously being introduced into areas where the virus is still present. These animals end up becoming infected. Even when the sows are in good health, and the piglets are weaned clean, if they enter a transition period with chronic PRRS due to mixed ages, it is impossible to control.

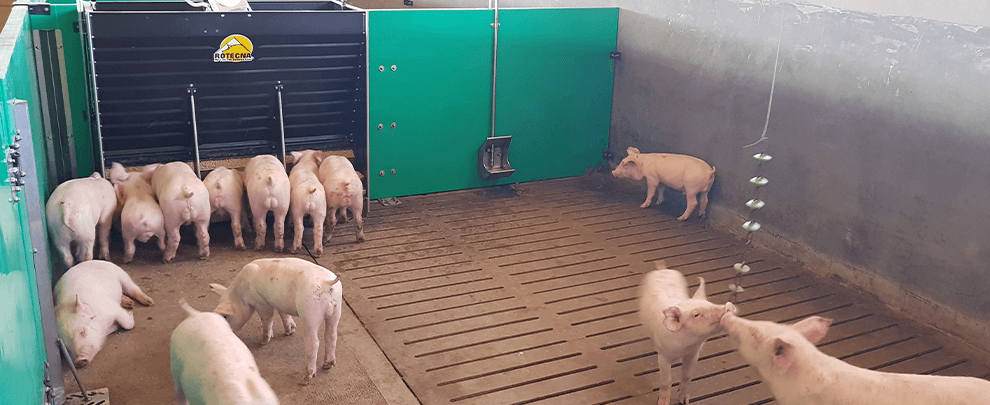

MEB>1s requires allocating sufficient space in the gestation area to ensure complete sanitary breaks. Photo: Rotecna.

What production or management indicators do you consider most helpful in evaluating whether a farm is taking advantage of the system's potential?

In most cases today, the main objective when transitioning to MEB>1s is to improve animal health. This implies enhancing production parameters (mortality, average daily gain, feed conversion ratio), especially in the transition and finishing phases. Improvements can also be achieved at the sow level. Indirectly, the improved health and organisational aspects of the system can also be reflected in reproductive performance, increasing the number of piglets weaned per sow per year. In many cases, the number of sows has been reduced when switching to MEB>1s, and even higher production volumes have been weaned with fewer sows.

From your experience, what are the most frequent mistakes when a farm switches from continuous to batch management? How can they be avoided?

Sometimes the change isn't planned well because the practical implications aren't anticipated. For example, when switching to MEB5s, a series of changes occurs that is entirely predictable and cannot be left to improvisation. The entire team must know what's going to happen, how the work will be reorganised, and what peak workloads there will be. It shouldn't be surprising that there will be busy days and quieter ones. To avoid this, the key is good planning from the beginning, a clear explanation of the system, and ensuring that all staff understand it and are prepared. Another problem is that not all available MEB> 1 options are consistently considered. These days, MEB5s are fashionable and the only option.

“The key to MEB>1s lies in proper planning from the outset, clearly explaining the system, and ensuring that all staff understand it and are prepared.”

What implications does this system have for work organisation and staff training, and what strategies help maintain discipline within the production calendar?

The MEB>1s, especially the MEB5s, are a double-edged sword. In this system, one week is for weaning, the next for breeding and farrowing, and then there are three weeks without major activities. On a commercial farm, this can be difficult to manage because the workload is concentrated in two weeks, while the other three are slower. It's essential to clearly explain to staff that the work will be very intense for about 2.5 weeks, followed by a quieter period. With good planning, peak workloads can be offset with days off, which many workers appreciate. Furthermore, this system reduces the impact of weekends or holidays, as peak periods are more concentrated and predictable. Staff training can also benefit. Working in batches requires the team to act in a coordinated manner. On a farm with 2,000 sows in five-week batches, where 500 sows can be bred at once, the entire team participates in each of the key tasks. This allows workers to learn all aspects of the production cycle while remaining under constant supervision, thereby improving versatility and efficiency. In any case, maintaining strict adherence to the schedule is fundamental in this system. During those two and a half weeks of peak activity, no one can afford to miss a shift. In other systems, such as MEB3s, MEB3/2, or MEB2.5s, the workload is distributed more evenly. The advantage of reducing weekend breeding or farrowing compared to MEB1s is maintained, which remains very beneficial from an organisational standpoint, especially during holidays.

Finally, what advice would you give to a producer who wants to start but is afraid of losing productivity during the transition?

If their farm has a serious PRRS Rosalia problem, every day that passes without action is a day lost. The situation needs to be carefully assessed, and, naturally, its severity determines the response. If the problem persists severely and chronically, there is no other alternative. I don't think many of those who have switched to MEB>1s regret it. Most probably regret not having done it sooner.